Chew on This: The Connection Between Probiotics and Alzheimer’s

Did you eat a healthy breakfast this morning? If so, you might have improved your brain health!

Our gut bacteria perform important functions for our digestion. They break down foods to create essential vitamins and nutrients that we need, and that our human cells aren't able to digest on their own. That includes creating signaling molecules used by the nervous system.

Image credit: Getty Images

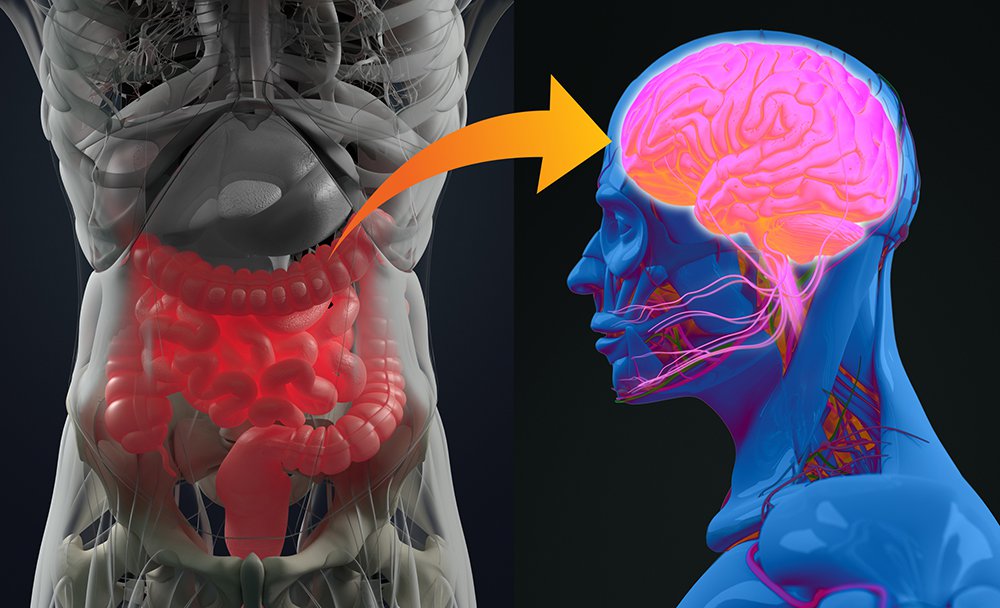

Recently, researchers have been studying these communication pathways between the digestive system and the brain, called the gut-brain axis. They are looking for clues as to how they might be able to slow or stop inflammation and cell death in the brain, and thereby prevent the progression of dementia and even Alzheimer’s disease.

Let’s take a big bite out of this science story to chew on the details about how prescription probiotics could lead to memory improvement.

Microbiomes

When you think of a biome, you might think of a rainforest or a desert, a collection of hundreds or thousands of types of plants and animals that all live together in a region with a certain climate and environmental conditions that is distinctive from another. In a smaller, but no less diverse way, we humans are each host to individual microbiomes, growing up to 10,000 species of microbes, including mostly bacteria, but also fungi, viruses, single-celled microbes called archaea and more.

Just like in a rainforest, it is the wild diversity of life throughout our bodies that allows us to survive and thrive. Our microbiota provides protection, nourishment and more. For example, many of the bacterial species living in our gut are responsible for digesting foods and producing essential vitamins and nutrients that our human cells aren’t capable of—and this starts at birth, with the first colonies of bacteria in our intestines that digest mother’s milk.

The average lifespan of a bacterial cell is around 12 hours, meaning that over the course of the months and years of our relatively long life, bacterial colonies grow and shrink, and entire species are lost and gained. This is where our choices can make big differences. In our gut, we can make a variety of choices to change the bacterial colonies living there.

Humans have relied on fermented foods as part of traditional diets and medicines for thousands of years, but it wasn’t until the World Health Organization defined probiotics in 2001—amidst rising scientific research on the gut microbiome—that awareness in the general public began to increase. Doctors began to educate patients more fully about some effects of antibiotic medications. Antibiotics kill off bacteria, or slow their growth, and are an effective treatment for bacterial infections, but they can also negatively affect good bacteria.

Image Credit: Getty Images

Over the last decade doctors have been recommending the addition of probiotics and prebiotics to their patients’ diets, especially while battling an infection. Probiotics, such as yogurt and fermented foods, contain good bacteria to help repopulate your gut. Prebiotics are foods which contain fiber and other nutrients that your gut bacteria need to survive. Your human cells might not be able to digest all of these, but your good gut bacteria need them to make things that your body depends on (like vitamin B12, which is only produced by bacteria).

And it isn’t just gut health that these bacteria are affecting because, as the saying goes, we are what we eat! When we drink a glass of warm milk at bedtime or eat a big turkey dinner, we feel sleepy (or at least relaxed) because they contain tryptophan. Tryptophan is a building block for neurotransmitters like serotonin (which affects mood) and melatonin (which can make you sleepy). As with most digestive processes, bacteria play a big role in turning that turkey dinner into neurotransmitters. So our gut may actually be controlling our brain, which is a new way of thinking about how these systems are connected!

Gut-Brain Axis

That thrilling sensation of butterflies in the stomach can happen when we’re nervous about a presentation or just saw the smile of someone special. That’s actually the sympathetic nervous system adjusting our digestive patterns in something like the fight-or-flight response. Essentially, this means our brain is preparing our gut for excitement and action rather than lazy rest and digestion.

For most of the last century, we’ve known that the brain could communicate with the gut. The brain has a lot of communication devices that it uses—kind of like how we have text, email, phone, social media, etc. Through nerves, immune cells, hormones and more, the brain influences intestinal function and digestion overall. The brain tells the digestive system to digest, to pause, to speed up or to slow down based on whatever information it has.

But does our gut talk to our brain? Absolutely!

Our gut talks to our brain through nerves and microbes, although that information is much newer and less well-studied. Our gut is ennervated with what’s called the enteric nervous system, an amazingly complex and understudied component of the peripheral nervous system. The vagus nerve (one of the 12 cranial nerves) serves as a highway of communication between the gut and the brain. And, as discussed earlier, the specific microbes in the gut can affect digestion of various foods leading to variations in neurotransmitters as well as chemicals which can lead to inflammation in the immune system and more. In fact, the gut-brain axis has been a promising target of research on many diseases typically thought to be psychiatric, and has even demonstrated that cognition itself may be affected by gut bacteria.

Research over the past decade has revealed increasing evidence that dynamic changes in the gut microbiota—such as those mediated by dietary habits—can alter brain physiology and behavior. Gut microbial changes can contribute to brain disorders such as pain, depression, anxiety, autism, Alzheimer’s diseases, Parkinson’s disease and stroke. But, not surprisingly, the connection is complex and will require intensive study into the future before real therapeutics can be developed.

Image Credit: Getty Images

Alzheimer’s

A recent article reviewed more than 100 studies on the role of the gut-brain axis and gut microbiota in the development of Alzheimer’s disease in order to figure out how exactly to use probiotics as a treatment. Aging alters the gut microbiome, and related factors may contribute to neuroinflammation leading to neuronal injury and death in the progression of this disease. A number of scientific studies have also noted that probiotics have a positive effect on patients (or lab animals) with Alzheimer’s disease.

The questions are: which probiotics worked and how and why were they beneficial? Examining the possible mechanisms behind those beneficial effects of probiotic treatments for the improvement of Alzheimer’s disease symptoms allowed researchers to specifically identify potent probiotic strains and formulations that can be developed for the management of Alzheimer’s disease. Probiotic treatments for disease will need to go through this sort of rigorous testing to identify which one or few strains of bacteria out of thousands of possibilities are the ones that need to be increased or decreased, and how best to do it.

Probiotics

So if there’s some pretty strong evidence supporting probiotics, why doesn’t everyone take them and believe in them? Here’s where the “snake oil salesmen” begin to muddy the scientific waters and make us all wonder about the science of probiotics.

Dietary supplements are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, so manufacturers began selling nutritional supplements and foods termed “probiotic” without the necessary human studies to support their claims. Armed with only the most basic information—that probiotics are good—the public began purchasing and consuming these products with mixed results. The reality is many of those products aren’t delivering on their promises, are falsely advertised and often are misrepresenting the science of probiotics. Many over-the-counter probiotics are not formulated to actually survive the acidic environment of the stomach and reach the intestinal system, thus they are basically useless. These effectiveness and regulatory problems lead to understandable skepticism of the health benefits of probiotics as the public feels conned.

Meanwhile, probiotics which are marketed as true drugs, are subject to rigorous regulations and government oversight. These probiotics represent the kind of medicine that is replicable in scientific research studies. That means you’ll need a prescription and to pay for them. This can feel silly when there’s a cheap version on the shelf but that lower-cost version isn’t regulated and might include ingredients that are good, bad or neutral.

Imagine that instead of filling your prescription for an antibiotic, you decided to eat some moldy bread and cheese hoping it contained enough penicillin to kill your strep infection. Obviously, the typical manufacturer doesn’t want to make you too sick to buy more of their product, so chances are that it’ll be mostly neutral effects, rather than ill, but you have no guarantees!

Bottom line is that there’s a lot more to our guts than we’ve previously considered. We might be mind-controlled by our digestive system! But as with most stories, this one is complex and still getting figured out. Now that is food for thought!