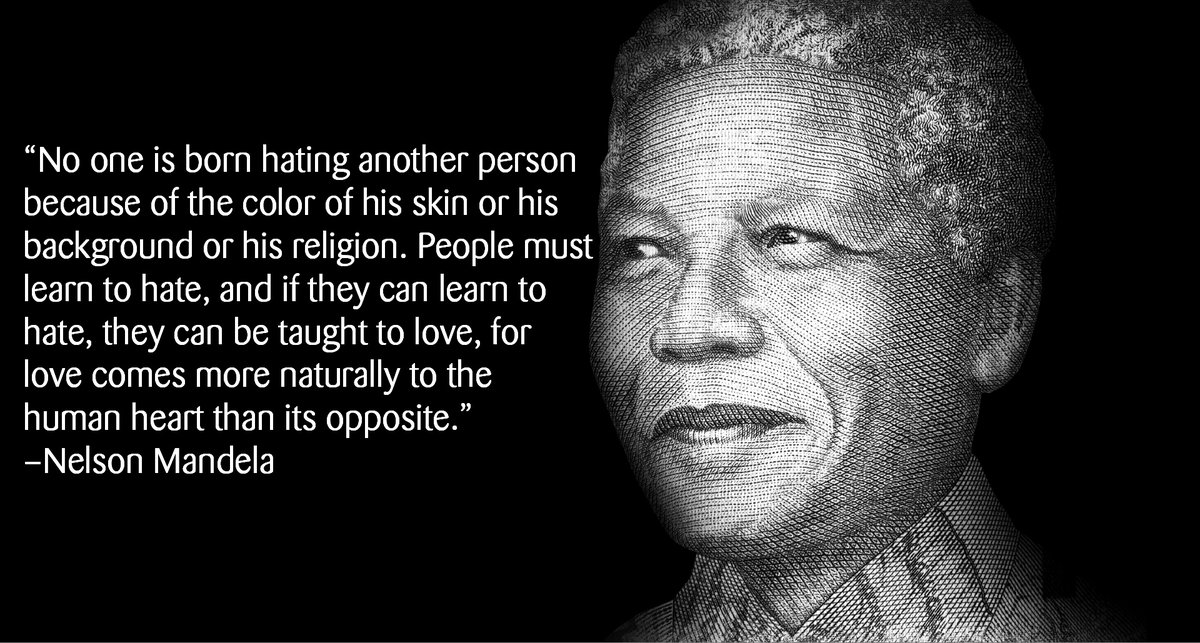

Are Mandela’s words scientifically true? Do we learn and unlearn hate and love? Can we unlearn the biases that we may have learned early in our lives?

Certain sections of our brains are tightly wired. Our sensory systems—taste, smell and vision—are closely linked to the insula, or disgust center of the brain, and the amygdala, or fear center. This is partly why more pungent vegetables like broccoli and cabbage are often targets of toddlers’ scorn and hatred.

As we age, we also learn how to fear through a phenomenon called “conditioning.” If you pair something unpleasant (in the lab, we often use electric shocks or loud noises when observing mice) with a more neutral stimulus like playing a simple tone, mice quickly learn to experience fear when they hear the neutral tone. My daughter, who is now 11, vehemently hates spiders. As a baby, she may have seen a spider, and I may have paired that with a loud noise (my own scream?) and swatting at it. This combination could have been the origin of her fear, reinforced through the media as she aged.

Once we recognize that something is to be feared or hated, our brains become increasingly hard-wired to identify other things that are similar and to recognize events that support things we’ve already learned. In other words, the more we hear and see a thing, the more we believe it is true. Unlearning that fear once it’s wired in is difficult business.

Our brain naturally attempts to sort things into distinct categories. It does this quickly and readily … whether we want it to or not. While very few categories exist innately, many categories we learn easily and readily. Is this yummy food? Is it a furry animal? Is this someone likely to take care of me? And then figuring out the categories of other people around us can be challenging.

When it comes to other beings of the same species, we—like most animals—show empathy and altruism toward those that look most like us. We care more about those that look like us than those who are different, and we expect them to take care of us in return. This is a consistent evolutionary phenomenon that exists in most animals observed.

Psychologists call this an “ingroup bias.” However, human skin color is not a sorting mechanism that comes as obviously as adults think. Many parents—including me—are initially shocked when their child refers to a stranger as a “black person” or “white person,” until they also reference a “blue” person and realize the child is talking about the color of the individual’s clothing, not their skin color. Children, who are able to see skin color, will sort and categorize their dolls, teachers and even strangers by any number of other features before skin color. Even once they are using skin color as an identifier, children happily play and interact with people of all skin colors and backgrounds without concern—until they are taught by an adult to associate negative attributes to a person’s skin color. Only then do we learn to put our entirely subjective idea of “race” into our ingroup and another into our outgroup. The outgroup has successfully been paired with something unpleasant, and a fear is born.

Image Credit: Getty Images

The historical concept of race continues today, this term highlights familiar—if incorrect—categories. Although there is little evidence of distinct human races from a biological or anthropological viewpoint, there is very solid scientific evidence of the impacts of the social construct of race. Race is commonly understood as a combination of physical, behavioral and cultural attributes, often confused with but distinct from ethnicity (defined more by language and shared culture), but is incredibly difficult to define, as it is based on outdated assumptions and data collected before the technology revolution.

There’s no neurobiological reason that people of different “races,” ethnicities and skin colors (as well as people with invisible differences such as religion, background or favorite sports team) can’t be re-sorted into your ingroup. Identifying these differences and promoting negative attitudes toward people with those differences is a learned behavior called racism. In other words, racism is learned.

So, how do we overcome racism with neuroscience? How do we learn to love those in our ingroups and outgroups? Although science does not have all the answers (and more work needs to be done) we do have data from experiments that show that people can overcome aversion to things they identify as threats through reducing the aversion to the perceived threat over time.

For example, in the lab, we would un-train the animal that has learned to fear a neutral tone by continuing to play the tone while also stopping the shocks that it fears. Over time, the animal realizes that any danger is past and that the tone is no longer a threat. Similarly, parents use this concept by serving vegetables at children's parties to associate them with good and pleasant times, thereby reducing the natural aversion children have to the bitter taste of vegetables.

We must first understand that our biases against a given group are real and are being reinforced by our brains all the time. Then, we can deliberately seek out opportunities to expand our ingroup to include previously excluded groups. Here are a few scientifically-supported ways to do this:

- Seek out conversations with people who seem different from you.

- Set up “playdates” (kids or adults; virtual or face to face) with people that could be considered part of your outgroup. Anything from a Zoom happy hour to a rendezvous at a local park or museum.

- Explore the boundaries of your ingroup and outgroup through personal reflection.

These positive interactions and self exploration will be noted by your brain, which will come to realize that the biases it had held onto are false.

Edited with permission from an editorial authored by Dr. Catherine Franssen published in the Roanoke Times on Oct. 7, 2017.

As a learning organization, the Science Museum of Virginia is committed to learning as much as we can to become a better organization. We will continue to look at what science can teach us and will be sharing things with you as we all learn together.