Cities and Health: Walking Through the Science

The Science Museum is always looking for ways to get guests, neighbors and curious folks across Virginia involved in community science initiatives. Why? Because there’s no shortage of topics and questions that need further exploration. Also, collaborating with community members on data-collection initiatives deepens their connection to science, a core aspect of our mission.

So it should come as no surprise that when a community science opportunity presented itself in 2020, the Science Museum’s David and Jane Cohn Scientist, Dr. Jeremy Hoffman, and Community Science Catalyst, Devin Jefferson, jumped at the chance to be involved. Working alongside collaborators from the University of Virginia and Virginia Tech, the team embarked on an innovative community science study exploring how walking in different neighborhood designs impacts our wellbeing, the results of which were recently published in the scientific journal Cities and Health.

The collaboration started when members of the University of Virginia’s School of Architecture published a paper on how retirees living in the William Byrd Senior Apartments across the street from the Science Museum reacted to short walks in vastly different neighborhood designs. Their results showed that participants who walked in the shadier, quieter setting had improvements in mood and happiness levels.

The Science Museum decided to build on that work. We combined their method of using heart rate sensors on smartwatches with our RVAir and urban heat exposure work. We wanted to see to what extent we could measure these effects in Richmond during the early part of the pandemic across a broader cross-section of ages and backgrounds.

In order to do that, we outfitted a group of volunteer community scientists with air quality, temperature, heart rate and other sensors. We asked them some questions about how they felt, and had them randomly assigned into groups to take two different walks near the Science Museum. One walk took volunteers into The Fan and around The Branch Architecture Museum's pocket park (the "urban green" walk, photo above right), while the other took volunteers down and back along Broad Street (the "urban gray" walk, photo above left).

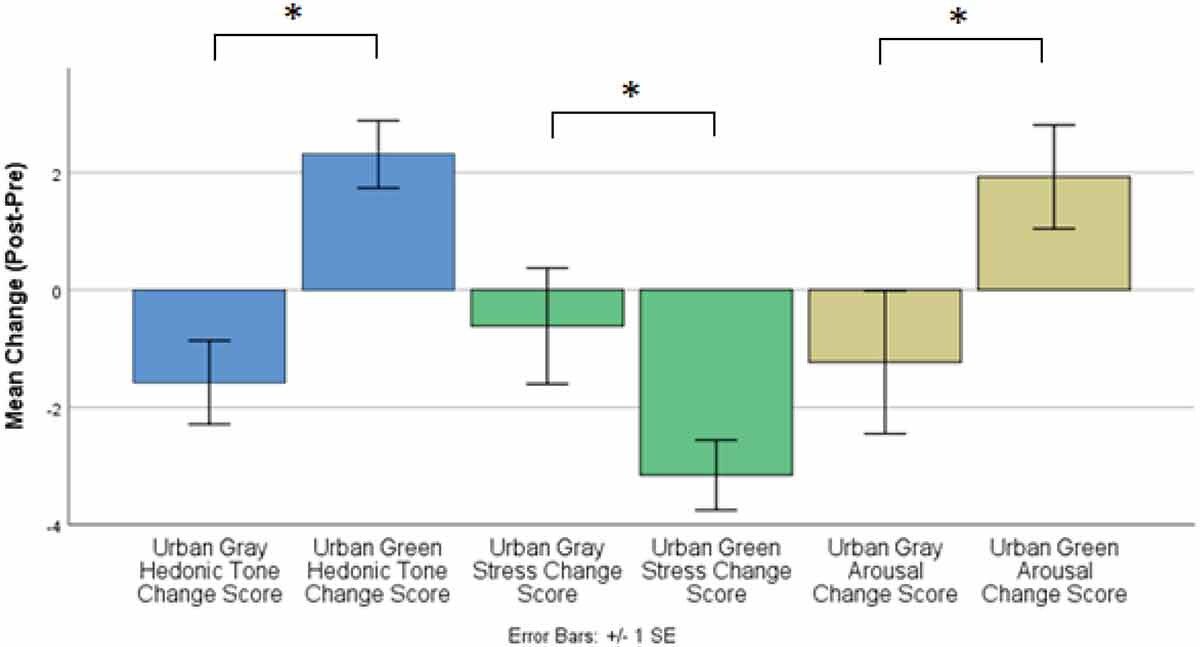

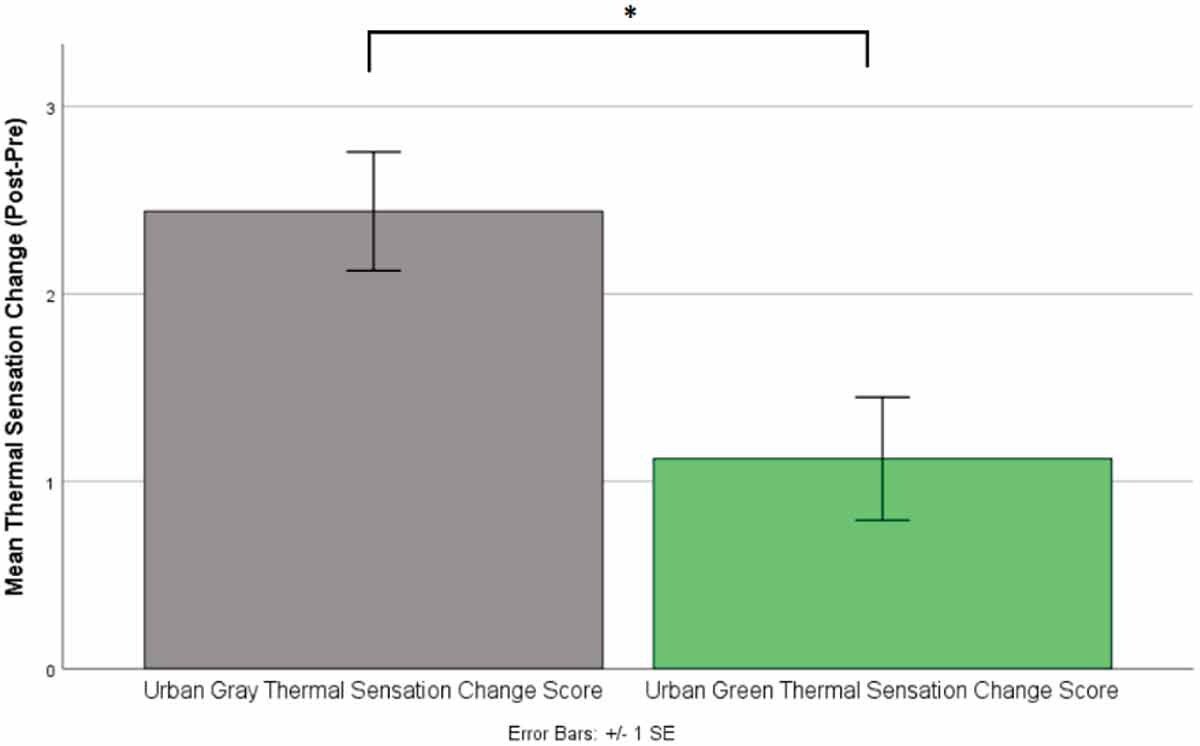

By comparing all of the data collected for each community scientist and between the groups, we could see how walking in either of these two environments affected several indicators of stress and mood. Walking in the urban green setting significantly improved community scientist mood and lowered indicators of stress (“urban green” change scores below), even when it was hot outside. By contrast, walking in the urban gray setting drastically increased community scientist exposure to heat, air pollution and traffic noise, resulting in higher stress indicators and thermal discomfort.

So, why does this matter? We know only about a third of Richmond's population engages in the Center for Disease Control's recommended amount of moderate-intensity activity per week. In addition, our Community Health Assessment identified elevated levels of mental health issues in Richmond.

Studying how neighborhood design impacted our volunteer walkers is consequential because walking in "urban green" settings has been shown to be extremely important for not only providing a safe place to engage in moderate-intensity activities (read that as exercise which helps improve health), but also for cognitive health and reducing feelings of depression and anxiety. Put another way: walking in a shady, quiet neighborhood can be like going to a therapist, trainer and outdoor thermal oasis all at the same time!

This research has a real-world, public health implication for our city as it grows. Applying these findings to how we design public spaces could help improve community wellbeing in the face of climate change and urban growth.

On an individual level, we can all work to spend a bit of our time whenever possible enjoying a greenspace. Beyond that, showing support for prioritizing the reallocation of public space to be developed into safe, quiet, shady pedestrian areas for everyone to enjoy–especially in areas that have been denied these resources–could go a long way to positively impacting public health as well as reaching climate change goals.