Question Your World: How Do Cities Handle Heat?

As our population grows, we will need more and more places for us humans to do our human things. This means, as we grow, we tend to convert natural spaces into developed areas. An urban environment is quite different from a natural landscape and thus has its own variables and concerns. The growth of urban spaces compounded with the changing climate is causing some scientists to take a look at how our urban areas interact with heat. Today’s big question explores urban heat islands by asking - how do cities handle heat?

You may have heard reports that, in July 2017, community scientists from GroundworkRVA, Portland State University, the Science Museum of Virginia, the City of Richmond Sustainability Office, Virginia Commonwealth University’s SustainLab, and the University of Richmond’s Spatial Analysis Lab went out and measured Richmond’s temperature during a heat wave. Using sensors attached to their cars, they were able to identify a 16°F difference between the warmest and coolest places in the city, at the same time on the same day!

During the last several summers, these hotter places in town have also had a higher rate of hospitalization and ambulance responses for heat-related illnesses and injuries. Consider for a second being ill and having to deal with a temperature difference of up to 16 degrees! Someone at risk of heat stroke could be much more vulnerable to heat-related issues, especially if they happened to live in a locally hotter part of the city than in a cooler area. Knowing about these areas is the first step to engaging citizens, spreading awareness, and beginning a dialogue with elected officials to find ways to address this public health concern. Providing more green spaces, trees for shade, and access to public water would be just a few ways to begin to enact change in some of the hotter neighborhoods.

The research showed that places in the city with little tree cover or greenspace were among the hottest areas. Think about Scott’s Addition with its massive asphalt parking lots and brick buildings compared with a place like the tree heavy areas of Dogwood Dell behind the Carillon – concentrations of human landscapes amplify heat, while our parks and shaded areas provide a cooler environment.

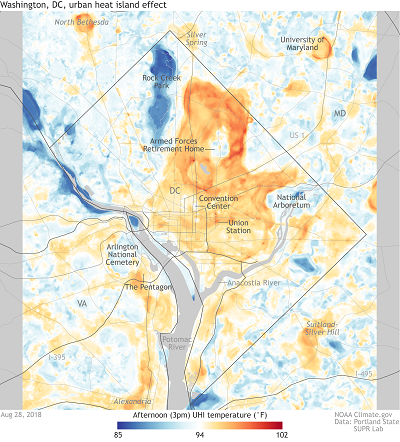

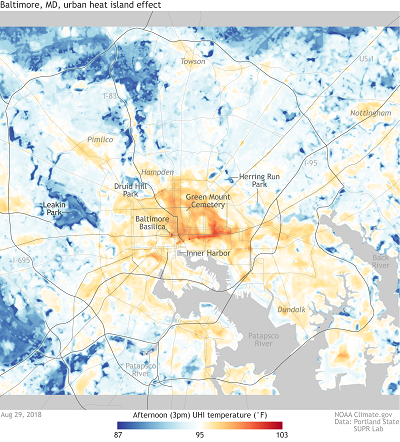

Well, that project was so successful that the Science Museum of Virginia and Portland State University were asked by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to do similar projects in Washington, DC, and Baltimore, MD, with help from local nonprofits groups, local government, and volunteers from other informal science centers.

The results? The citizen scientists discovered differences of up to 17°F between the warmest and coolest areas in both cities! Both cities, like Richmond, have indicated that battling this heat – and the co-benefits of addressing it, like cleaner stormwater and fresher air – will become a major focus of their city plans in the near future.

That’s a science to civics to action win!