Question Your World: What Is Pollution Inequity?

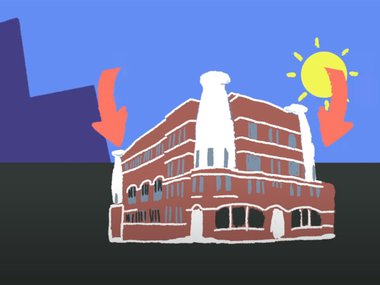

Science and human health often go hand in hand. We’ve shared our Urban Heat Island project with you many times as just one example of how science gives us a window into the dynamic relationship between us and the world around us. We certainly share one sky, but there are people and places that habitually get more exposure to pollution than others. A new study on this exact issue poses a great question for us to ask today: What is pollution inequity?

The world we've built is a vast network of relationships, where actions at one place or by one person can have distant, but absolutely observable, impacts on another. Studying those relationships can be complex and very involved, but knowing these relationships is beyond valuable for our ever growing and changing world. A team of researchers just released findings showing the differences in socio-economic groups that inhale more air pollution compared to those that cause more air pollution, something they've named “pollution inequity”

This huge study started with something microscopically small, PM2.5, which stands for Particulate Matter that’s 2.5 micrometers or smaller. These particles can be farm dust and ash from car tailpipes. Now the big question is: who’s causing this pollution and who’s experiencing it the most?

So, how does one collect the variables involved in such a broad-ranged objective? For this study, researchers tabulated industries that cause PM2.5 pollution, the regions and populations that are impacted most by this pollution, and the consumer base that's driving these industries. Their data suggest that income – as it relates to consuming goods from the industries that cause PM2.5 pollution – is an important determinate to how much pollution a person causes.

Image credit: Getty Images

The research took things a step further and looked at differences between racial-ethnic groups. To determine the “pollution inequity,” researchers looked at the difference between a racial-ethnic group’s exposure to PM2.5 and that group’s contribution to the creation of PM2.5. One of the results shows that people who identify as non-Hispanic white experience 17% less air pollution than they produce, while black and Hispanic citizens experience 56% and 63% more air pollution than they produce.

Being a consumer is a pretty passive but impactful process. While we may be far removed from the things we’re buying, their production and journey often involves many opportunities to cause pollution. Simultaneously, the pollution output is often distributed to places that have higher concentrations of poorer populations. The relationship between consumers and pollution and all the complex steps involved, is exactly what this study digs into.

Consider that nearly all of our human consumption needs currently involve some sort of pollution output. For example, simply purchasing an avocado involves PM2.5 pollution from the farm and packaging center, national or international distribution, regional grocer storage, neighborhood store delivery, and then finally we drive it home. With each step, we are contributing pollution in different capacities. The average meal at our table has traveled nearly 1,500 miles to get to us. Multiplying this by the ever growing numbers of neighborhoods, cities, and nations on our planet helps put some perspective on the scope of variables and pollution output we're truly looking at.

Because 63% of all deaths caused by environmental stresses and 3% of all fatalities in the nation are due to frequent exposure of PM2.5, scientists are hopeful that this study will encourage dialogue between citizens, developers, planners, and elected officials on how to further understand and address these pollution equity issues at regional levels.

Adding neighborhood air quality monitors, planning green space in new developments, reducing one’s use of inefficient fuel-based transportation, composting, and many other options can be explored to lower one’s pollution footprint.

Another great reminder that it’s all connected.