An Unjust Evolution

By Todd Lookingbill, associate professor of geography and the environment, University of Richmond

2020 was the third warmest year on record globally, with the six warmest having all occurred since 2015. But not all locations on the planet are experiencing the same level of warming. Cities are getting hotter faster than their surroundings as part of a phenomenon known as the urban heat island effect. And within cities, communities of color and other historically marginalized communities are far more likely to be living within urban heat islands and suffering associated negative health consequences, as the Museum has previously shown.

A flurry of recent legislative proposals and executive actions have targeted the intertwined crises of climate change and environmental injustice. The environmental health inequalities exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic have further highlighted the urgent need to address these problems. Devising effective policies requires a deeper, science-based understanding of the geographic variability of air and climate in our nation’s cities.

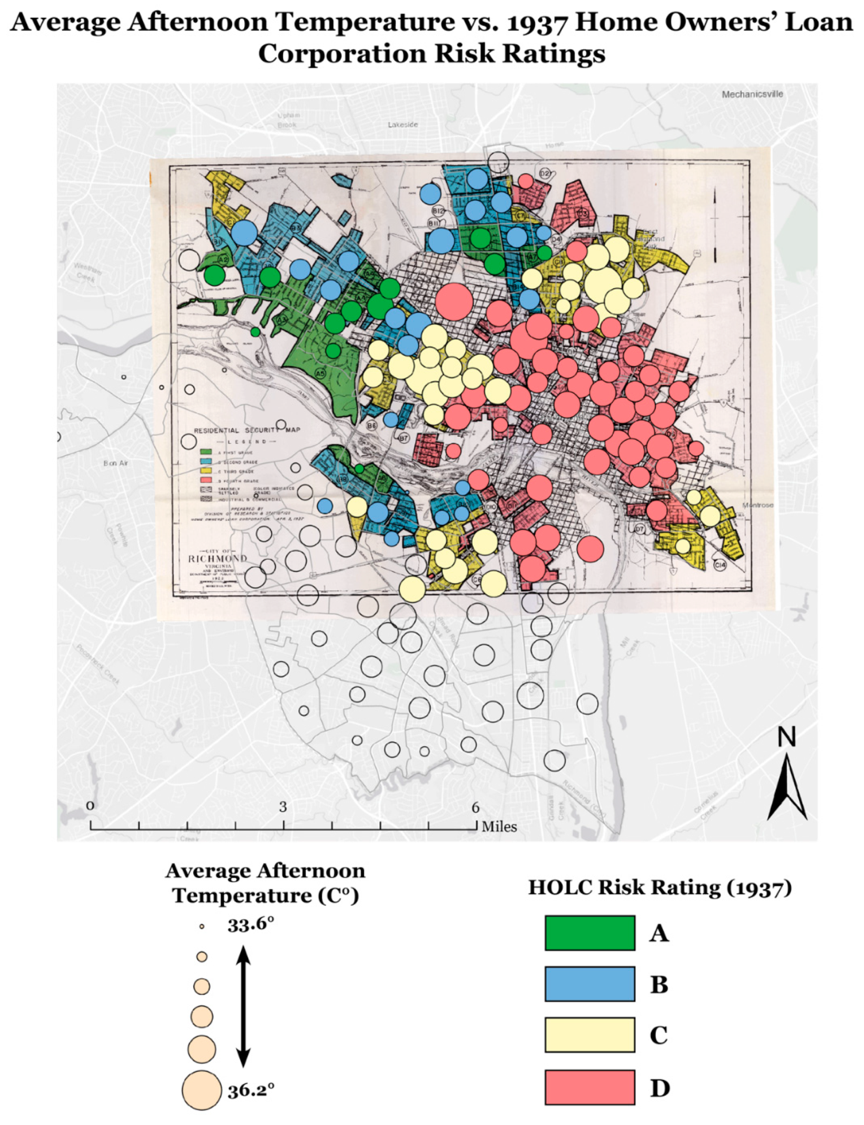

1937 Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) risk ratings throughout Richmond, VA. Average afternoon temperature is overlaid, with larger circles indicating higher temperatures.

Two papers published by the University of Richmond in collaboration with the Museum explore the relationships between temperature, air quality, socio-demographic factors, and historical planning decisions for the City of Richmond. The papers are part of a special issue on Environmental Justice and Sustainability in the journal Sustainability, and will be presented at the American Association of Geographers Annual Meeting in April. The research contained within the papers was spearheaded by University of Richmond students Andre Eanes, Kelly Saverino, Emily Routman, and Rong Bao.

The first study continues ongoing research on urban heat island effects in Richmond. In 2017, a broad coalition of Richmond scientists and citizens conducted a detailed mapping of areas of high thermal stress in the city. The study identified differences in temperature as high as 16° F among different neighborhoods in Richmond.

University of Richmond students setting up the air quality equipment. Photo courtesy of Todd Lookingbill.

In early 2020, the Museum published a related study linking satellite-derived estimates of summertime surface temperatures within 108 US cities to the long-lasting influence of discriminatory housing policies such as redlining in the 1930s and 1940s.

This new paper published in February combines information from the 2017 community field mapping of heat wave air temperature in Richmond with historical data on the zoning and redlining practices that barred black and minority groups from securing homes. Sites of extreme heat identified in the study include areas that were historically redlined, indicating the persistent legacy of these destructive policies. In tracing the unjust evolution of this urban landscape, neighborhoods rated as HOLC Risk Rating “C: Definitely Declining” or “D: Hazardous” were found to have fewer trees, more dark impervious surfaces, and fewer public greenspaces, all physical drivers of higher temperatures.

Using socio-economic data from the American Community Survey, the research team found significant relationships between temperature and more recent measures of household income and public transportation use. Black communities and those living below the poverty line also were disproportionately located in the hottest areas of Richmond, and in turn more exposed to the negative consequences of extreme heat, compared to their wealthier, white counterparts. Notably, in comparing the economic data over the past eight years, disparities are getting worse, not better.

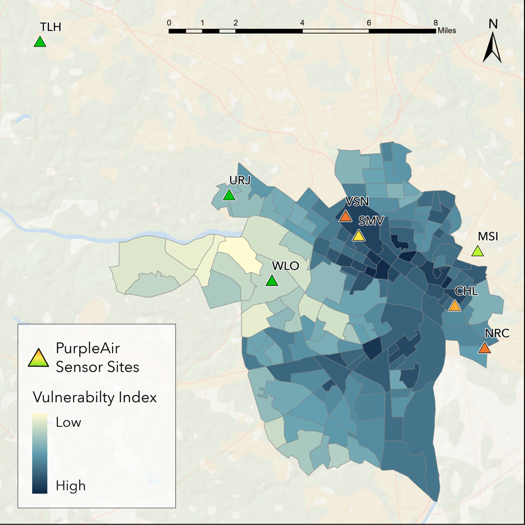

Spatially, sites exhibiting higher temperatures (left) also had higher PM2.5 concentrations (right), with vulnerable communities in the east end and more intensely developed parts of the city experiencing significantly higher temperatures and PM2.5 concentrations than the suburban neighborhoods in the west end. Green corresponds to sample sites with lower values, while higher values are shown in red. The locations of the monitoring sites are projected onto an underlying vulnerability index.

The second study investigates the connection between temperature and air quality in Richmond. Degraded natural areas in cities benefit less from “environmental amenities,” such as the cooling effects of green space and removal of pollutants leading to cleaner air and water. The concern is that with fewer of the environmental benefits provided by trees and other native vegetation, vulnerable urban communities may suffer from a so-called “double whammy” of both extreme heat and poor air quality.

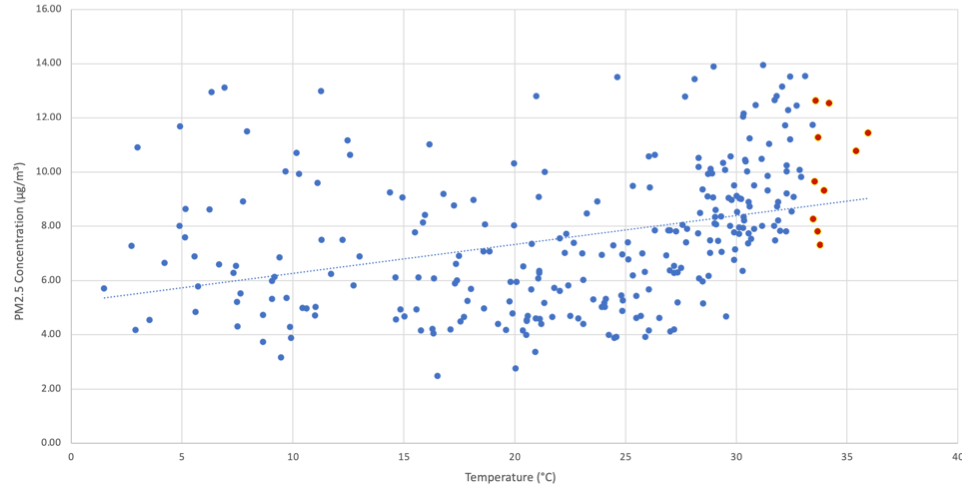

As a first test of the potential spatial overlap between air pollution and temperature stress, the researchers installed eight air quality sensors at residences and business throughout Richmond representing a range of socioeconomic and physical environments, including different types of land use, amounts of tree cover, population densities, and racial and ethnic composition. Data from these sensors collected during the ten hottest days of the summer in 2019 demonstrate that the persistent, environmental inequities that we’ve collaboratively discovered for heat also extend to air quality, with low-income communities and communities of color experiencing elevated levels of air pollution during heat waves. The Museum’s RVAir program continues to investigate these issues with community partnerships.

Air quality (PM2.5 concentration) is correlated with temperature in Richmond such that the ten hottest days of 2019 (shown in orange) also had some of the year’s highest levels of air pollution.

Studies like these demonstrate how environmental stressors correlate with historical legacies that have led to unequal distributions of green space and other land-use factors in cities. In response, cities need innovative and sustainable planning solutions.

The City of Richmond has committed to ongoing efforts to create healthier, more resilient, and equitable communities. To accomplish these goals, Richmond and cities like it require more data to guide their justice-driven mitigation strategies. More than 30 real-time air monitoring sensors have been installed in and around Richmond. This network will provide much needed additional data on the inequities in particulate matter and extreme temperature for future planning initiatives.